The Book in 3 Sentences

Tiago Forte’s Building a Second Brain book is a guide to developing a productivity system that helps you better manage information and improve your creativity, productivity, and ability to generate insights.

Forte teaches readers to create a digital system, or a “second brain,” to help them capture, organize and structure their thoughts, ideas, and to-dos.

The heart of the Second Brain process is a workflow called CODE: Capture, Organize, Distill, and Express.

Impressions

I enjoyed the book overall and the CODE process he outlines in the book.

I’m a big fan of tool-agnostic workflows and philosophical frameworks for productivity. There’s a tendency for people to be tool-obsessed, but it’s better to be able to describe your workflow in plain English, then select a tool that supports that workflow.

For a book about summarization, it’s wordy, and there are a lot of anecdotes and tangents. This additional background and context might be helpful to those beginning notetaking, but as someone following Forte for several years, I found them lengthy and unnecessary.

Who Should Read It?

Someone completely new to productivity and notetaking

Someone wanting an overview of Forte’s thinking. It’s a good summarization of the material he’s put out over the past several years.

Someone looking for a good tool agnostic notetaking workflow framework

Someone who liked similar books such as Getting Things Done by David Allen or How to Take Smart notes by Sönke Ahrens.

How the Book Changed Me

This book inspired my current notetaking system. I organize my notes based on specific projects and categorize them into broad life areas, similar to the PARA project organization structure he proposes.

I loosely follow the progressive summarization idea but only sometimes do the second-pass highlighting. It’s hard to be selective in what you capture while still needing enough context to do two passes of highlighting. I plan on being selective but initially capturing more context, for example, whole paragraphs instead of individual sentences.

The project checklist and weekly review are good ideas that I incorporated into my notetaking system.

I like the idea of having different “modes” of working, like “convergent” mode and “divergent” mode. In divergent mode (Capture and Organize), you cast a wide net and let your curiosity guide you. In convergent mode (Distill and Express), you focus on the task at hand. This book encouraged me to minimize mode shifts while working. For example, instead of finding an article, summarizing it, then finding another article, I would capture a bunch, then summarize them during a dedicated time.

My Top 3 Quotes

What’s the point of knowing something if it doesn’t positively impact anyone, not even yourself?

Your job as a notetaker is to preserve the notes you’re taking on the things you discover in such a way that they can survive the journey into the future. That way your excitement and enthusiasm for your knowledge builds over time instead of fading away

PARA isn’t a filing system; it’s a production system. It’s no use trying to find the “perfect place” where a note or file belongs. There isn’t one. The whole system is constantly shifting and changing in sync with your constantly changing life.

Summary + Notes

CODE

Capture

The second brain process starts by capturing information that resonates with you from external sources or your internal moments of insight.

Capturing information frees you from the burden of trying to remember everything and helps you focus on the higher-level creative process.

Examples of external sources to capture

- Highlights: insightful passages from books or articles you read

- Quotes: memorable passages from podcasts, audiobooks, or videos

- Bookmarks and favorites: links to content you found on the internet or social media

- Meeting notes: notes or ideas from meetings or calls

- Images: photos or other images you find inspiring and interesting

Examples of internal sources to capture

- Stories: things that happened to you or someone else

- Insights: realizations or random ideas that pop into your head

- Memories: experiences from your life that you don’t want to forget

- Reflections: personal thoughts and lessons

How to decide what to capture

You want to avoid capturing too much information or too little, so Forte offers insights on deciding what to capture.

In a piece of content, some parts are more valuable than others. Many people start by capturing too much. You shouldn’t be saving entire articles to your second brain.

The primary advice is to capture things that resonate with you

Ask yourself:

- Does it inspire me?

- Is it useful?

- Is it personal?

- Is it surprising?

Favorite questions

Another technique that helps decide what to capture is having a list of “favorite questions” and capturing any information that relates to these questions.

The scientist Richard Feynman used this technique.

You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!”

Ask yourself, “What are the questions I’ve always been interested in?”

This could include grand, sweeping questions like “How can we make society fairer and more equitable?” as well as practical ones like “How can I make it a habit to exercise every day?”

It might include questions about relationships, such as “How can I have closer relationships with the people I love?” or productivity, like “How can I spend more of my time doing high-value work?”

Examples of favorite questions

How do I live less in the past, and more in the present?

How do I build an investment strategy that is aligned with my mid-term and long-term goals and commitments?

What does it look like to move from mindless consumption to mindful creation?

How can I go to bed early instead of watching shows after the kids go to bed?

How can my industry become more ecologically sustainable while remaining profitable?

How can I work through the fear I have of taking on more responsibility?

How can my school provide more resources for students with special needs?

How do I start reading all the books I already have instead of buying more?

How can I speed up and relax at the same time?

How can we make the healthcare system more responsive

Capture tools

You should leverage technology to make it easier to capture information and automatically send it to your second brain.

- Note-taking apps let you store, search, and organize your content.

- Read-it-later apps let you save interesting articles for later and highlight passages in them.

- Ebook readers often let you highlight and export those highlights to your second brain.

- Web clippers let you save and highlight parts of web pages.

- Podcast clippers let you save excerpts and transcribe them to text.

- YouTube capture tools let you save portions of YouTube videos as transcripts to your notes.

- Voice memos let you record your voice and transcribe it to text for your notes.

Organize

As you capture information, you’ll need a system to organize and retrieve it.

You want to avoid following elaborate rules for organizing your information. Your system needs to be simple and flexible. We don’t want to spend more time organizing our information than putting it to use.

You might be tempted to organize things by “subjects,” but this is suboptimal. For example, you might consider putting an article in a “psychology” folder. But under what circumstances will you scroll through all your articles related to the broad subject of “psychology”?

Organizing your information around focused projects and broad areas of your life is better.

Forte proposes an organization structure called PARA, which stands for Project, Area, Resource, and Archive.

PARA

Projects

Short-term efforts in your work or life that you’re working on now.

Projects have a beginning and an end.

Projects also have a clear outcome needed for the project to be considered “done.”

Examples of projects

- Projects at work: Complete web-page design; Create slide deck for conference; Develop project schedule; Plan recruitment drive.

- Personal projects: Finish Spanish language course; Plan vacation; Buy new living room furniture; Find local volunteer opportunity.

- Side projects: Publish blog post; Launch crowdfunding campaign; Research best podcast microphone; Complete online course.

Areas

Projects are the main focus of the PARA system, but not everything is a project.

Some things in our lives, like “finances,” don’t have a definite end date and require an ongoing effort; these are called areas.

Usually, projects are associated with an area.

| Project | Area |

|---|---|

| Lose 10 pounds | Health |

| Publish a book | Writing |

| Save 3 months of expenses | Finance |

| Create app mockup | Product design |

| Develop Contract Template | Legal |

Examples of areas

- Activities or places you are responsible for: Home/apartment; Cooking; Travel; Car.

- People you are responsible for or accountable to: Friends; Kids; Spouse; Pets.

- Standards of performance you are responsible for: Health; Personal growth; Friendships; Finances.

- Departments or functions you are responsible for: Account management; Marketing; Operations; Product development.

- People or teams you are responsible for or accountable to: Direct reports; Manager; Board of directors; Suppliers.

- Standards of performance you are responsible for: Professional development; Sales and marketing; Relationships and networking; Recruiting and hiring.

Resources

Resources are a catchall for everything that isn’t an area or project.

It’s a personal library of references, facts, and inspiration.

What topics are you interested in? Architecture; Interior design; English literature; Beer brewing.

What subjects are you researching? Habit formation; Notetaking; Project management; Nutrition. What useful information do you want to be able to reference?

Vacation itineraries; Life goals; Stock photos; Product testimonials.

Which hobbies or passions do you have? Coffee; Classic movies; Hip-hop music; Japanese anime.

Archives

Archives are things you’ve completed or put on hold.

For example:

- Completed or canceled projects

- Areas of responsibility that are no longer relevant

- Resources that are no longer relevant, for example, hobbies you’ve discontinued

How to decide where to put notes

The moment you decide to capture something isn’t the best time to organize it.

You need more time to consider the note before organizing it. Also, it increases the friction in capturing notes.

You should separate capture and organize into distinct steps.

Here’s a workflow for deciding where to put a newly captured note:

-

In which project will this be most useful?

-

If none: In which area will this be most useful?

-

If none: Which resource does this belong to?

-

If none: Place in archives.

You are always trying to place a note or file not only where it will be useful, but where it will be useful the soonest.

Don’t organize ideas where they came from; organize them based on where they’re going and what projects they’re relevant to

PARA isn’t just about organizing your notes but also about identifying the structure of your life.

Distill

It’s important to distill notes to their most essential points so they are helpful in the future. Summarizing helps you quickly refresh your memory on a note without rereading the whole thing.

You don’t have to go through all the layers. You can tune the amount of summarization you do based on how important the note is and how much time you have.

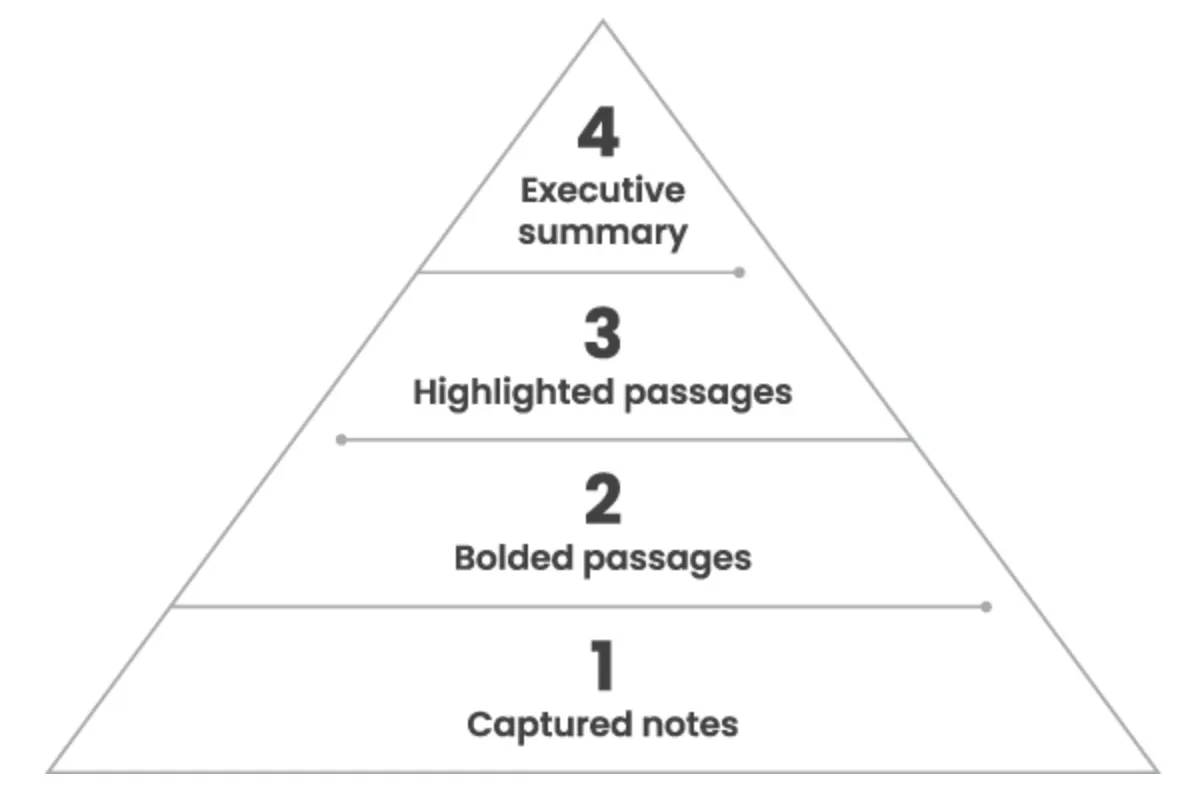

Progressive Summarization

Forte’s progressive summarization workflow helps you distill notes down to the most important points

Highlight the main points of a note

Highlight the main points of those highlights

And so on, distilling the essence of a note in several “layers.”

Layer one - Captured notes

Layer one is the excerpts of the articles you’ve captured.

Don’t try to capture the entire article.

Layer two - Bolding the most important parts

Layer two is where you bold the main points of your captured note: phrases that capture the essence of what the author is trying to say.

This step and the subsequent steps should be done when you have time for focused work, not at the time of capture.

These bolded passes are much faster to look back on than reading the entire article or your captured excerpts. It might only take a minute to refresh your memory instead of several minutes reading your full excerpts.

Layer three- Highlighting the bolded passages

Layer three highlights only the most critical points of the bolded passages from layer two.

This optional step is reserved for particularly long, interesting, or valuable notes.

These highlights are often just a few sentences or half sentences from everything you’ve captured.

Layer four - Executive Summary

The executive summary is a few bullet points at the top of your note summarizing the article in your own words.

This is usually only done for your most valuable notes, which you return to often.

Common Mistakes

Highlighting too much

Don’t highlight paragraph after paragraph of text or capture entire books or articles.

Each layer in Progressive Summarization should only include about 20% of the previous layer.

Highlighting without a purpose in mind

When should you be doing progressive summarization? When you are getting ready to create something

It takes time to distill your notes, so wait until you have a clear purpose. Otherwise, you’re investing significant time without knowing if it will pay off.

One rule of thumb is to make the note a little more discoverable every time you “touch” it by summarizing or adding a commentary.

Making highlighting difficult

Don’t overthink highlighting; rely on your intuition.

Use tools that make highlighting easy.

Express

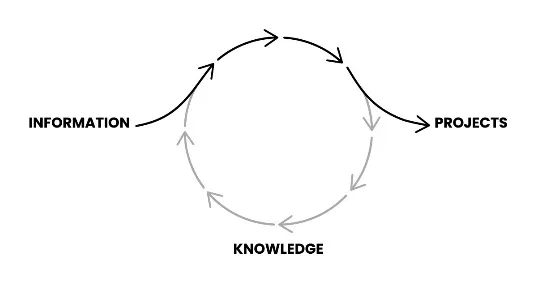

The ultimate goal of the system is to produce creative work and share it

The system is meant to set you up for success by leveraging your prior notes and work instead of reinventing the wheel every time you start something.

Examples of previous work you can leverage:

- Distilled notes: Books or articles you’ve read and distilled.

- Outtakes: The material or ideas that didn’t make it into a past project but could be used in future ones.

- Work-in-process: The documents, graphics, agendas, or plans you produced during past projects.

- Final deliverables: Concrete pieces of work you’ve delivered as part of past projects, which could become components of something new.

- Documents created by others: Knowledge assets created by people on your team, contractors or consultants, or even clients or customers, that you can reference and incorporate into your work.

How to resurface your past work

Search

Digital notetaking systems have a considerable advantage over physical systems: you can search their entire contents in less than a second.

This should be the first retrieval method you turn to, and it’s most beneficial when you already know what you’re looking for.

Browsing

If you’ve followed the second brain system, you already have your notes categorized by projects and areas.

Browsing is slower than search but lets you gradually hone in on the information you’re looking for

It’s helpful to take advantage of sorting, such as by date created.

Tags

Tags allow you to apply labels to notes regardless of location.

The problem with folders is that they can silo information, so tags are good for cross-cutting information and sparking interesting connections.

You might have a frequently asked question page for a project and tag it with FAQ. Then you can see the different FAQs across different projects.

The downside of tags is they require a lot of energy compared to searches and folders.

Serendipity

Sometimes a connection will jump out at you.

We can’t plan for this, but we can create conditions where it is more likely to happen.

One tip is to keep your focus broad when using the previous retrieval methods. Don’t just search in a specific folder; look through related folders too.

You may want to look through five or six of your PARA folders, which you’ve ideally already summarized, so that it won’t take too much time.

Also, you can use visuals to amplify serendipity. Save images as well as text notes.

Another powerful method is sharing your ideas with others. Feedback from others is unpredictable. They may be uninterested in something you think is fascinating or find something you think is obvious to be mind-blowing.

Other people can give you valuable feedback, such as pointing out aspects of your ideas or sources to consider.

Essential notetaking habits

How do we create sustainable habits and routines to build “compound interest” from our projects, notes, and knowledge?

Project Checklists

Ensure you start and consistently finish your projects leveraging past work.

The two most important moments in projects are when you start and finish them.

Since these moments are so important, you should have a defined process.

Project kickoff checklist

1. Capture your current thinking on the project

Create a dedicated note for the project and start brainstorming

This is a messy step where you should consider potential approaches, how it relates to other topics, people you should consult, etc.

Forte has a lists of questions he asks himself:

What do I already know about this project?

What don’t I know that I need to find out?

What is my goal or intention?

Who can I talk to who might provide insights?

What can I read or listen to for relevant ideas?

2. Review notes from folders and tags

Look through existing notes that could be relevant to the new project.

Browse through a handful of folders that contain summarized notes

3. Search for related terms across all folders

Search through your notes, which are more focused and higher quality than the stuff on the internet

4. Tag relevant notes to the project

You can use the features from your notetaking app to tag, link, or move relevant notes to the project.

5. Create an outline of collected notes and plan the project

Create an outline that makes it clear what you should do next

This should be a plan for tackling the project rather than starting the actual execution.

The first pass of outlining should only take 20-30 minutes.

For an essay, these are the main points or headings of the final piece.

If it’s a collaborative project, you should outline each person’s objectives and areas of responsibility.

More ideas for your project kickoff checklist

Answer premortem questions:

What do you want to learn?

What is the greatest source of uncertainty or most important question you want to answer?

What is most likely to fail?

Communicate with stakeholders

Explain to your manager, colleagues, clients, customers, shareholders, contractors, etc., what the project is about and why it matters.

Define success criteria:

What needs to happen for this project to be considered successful?

What are the minimum results you need to achieve, or the “stretch goals” you’re striving for?

Have an official kickoff:

Schedule check-in calls, make a budget and timeline, and write out the goals and objectives to make sure everyone is informed, aligned, and clear on what is expected of them. I find that doing an official kickoff is useful even if it’s a solo project!

Project completion checklist

Completing a project is unique because it is a rare moment when something ends.

1. Mark project as complete

When all the tasks as done, mark the project as complete in your notetaking app

2. Cross out the associated project goal and move to “Completed” section.

Review the goal of the project and reflect on how it panned out

If you were successful, why? What should you repeat next time?

If you fell short, what happened? What can you change to avoid making the same mistakes?

3. Review and organize parts that could be reused

Often components of your projects can be reused in the future.

For example, a web page design could be used as a template for future sites, an agenda for a one-on-one performance review, or interview questions you used for hiring.

4. Move project to archives across all platforms.

Archive the project to get it out of the way and avoid it cluttering up your environment

5. If canceled or paused, record current status

If you cancel or postpone a project, you can archive it but mark the current status with some comments.

For example, could you describe your last action and why you postponed it?

More ideas for project completion checklist

Answer postmortem questions:

What did you learn?

What did you do well?

What could you have done better?

What can you improve for next time?

Communicate with stakeholders:

Notify your manager, colleagues, clients, customers, shareholders, contractors, etc., that the project is complete and what the outcomes were.

Evaluate success criteria

Were the objectives of the project achieved?

Why or why not?

What was the return on investment?

Tie up loose ends

Send any last emails, invoices, receipts, feedback forms, or documents

Celebrate

Celebrate your accomplishments with your team or collaborators so you receive the feeling of fulfillment for all the effort you put in.

Weekly and Monthly Reviews

Periodically review your work and life and decide if you want to change anything.

The idea of weekly reviews comes from David Allen’s book Getting Things Done

Weekly review template

- Clear email inbox

- Check calendar

- Clear computer desktop

- Clear notes inbox

- Choose my tasks for the week

Monthly review template

- Review and update goals

- Review and update project list

- Review areas of responsibility

- Review someday/maybe tasks

- Reprioritize tasks

Noticing Habits

Notice small opportunities to edit, highlight, or move notes to make them more discoverable for your future self.

It takes too much work to stop and organize everything all at once, and it’s easier to add and manage notes a little bit at a time while living our lives.

- Noticing that an idea you have in mind could potentially be valuable and capturing it instead of thinking, “Oh, it’s nothing.”

- Noticing when an idea you’re reading about resonates with you and taking those extra few seconds to highlight it.

- Noticing that a note could use a better title and changing it so it’s easier for your future self to find it.

- Noticing you could move or link a note to another project or area where it will be more useful.

- Noticing opportunities to combine two or more notes into a new, larger work so you don’t have to start it from scratch.

- Noticing a chance to merge similar content from different notes into the same note so it’s not spread around too many places.