What’s it About

John Steinbeck sets out on a road trip across America with his standard poodle, Charley, in search of “the character of the country.”

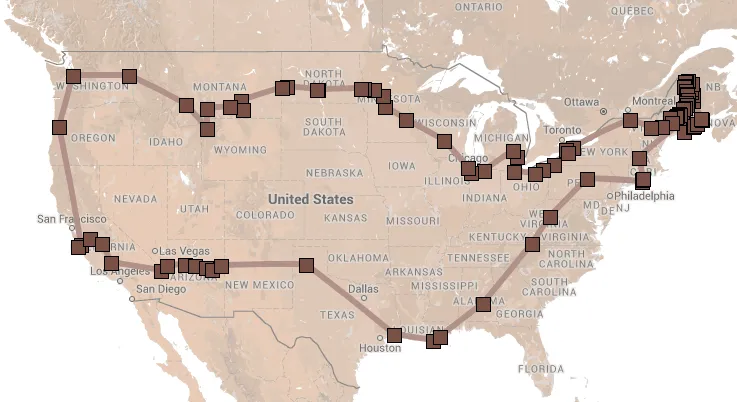

He starts in the Northeast and heads West, eventually heading down to the deep South. Along the way, he meets a variety of people and experiences a wide range of cultures.

Steinbeck wrote that he was moved by a desire to see his country on a personal level since he had only experienced it through the media and secondhand accounts.

How I Discovered It

I was looking up books by John Steinbeck and picked one that was shorter and more fun. East of Eden was too overwhelming in terms of scope and number of characters for me.

Thoughts

I enjoyed the book overall, especially the relationship with the poodle Charley.

The book gives a good snapshot of 1960s America.

My Top 3 Quotes

Once a journey is designed, equipped, and put in process, a new factor enters and takes over. A trip, a safari, an exploration, is an entity, different from all other journeys. It has personality, temperament, individuality, uniqueness. A journey is a person in itself; no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us. Tour masters, schedules, reservations, brass-bound and inevitable, dash themselves to wreckage on the personality of the trip. Only when this is recognized can the blown-in-the-glass bum relax and go along with it. Only then do the frustrations fall away. In this a journey is like marriage. The certain way to be wrong is to think you control it.

The redwoods, once seen, leave a mark or create a vision that stays with you always. No one has ever successfully painted or photographed a redwood tree. The feeling they produce is not transferable. From them comes silence and awe. It’s not only their unbelievable stature, nor the color which seems to shift and vary under your eyes, no, they are not like any trees we know, they are ambassadors from another time

A kind of second childhood falls on so many men. They trade their violence for the promise of a small increase of life span. In effect, the head of the house becomes the youngest child. And I have searched myself for this possibility with a kind of horror. For I have always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness. I’ve lifted, pulled, chopped, climbed, made love with joy and taken my hangovers as a consequence, not as a punishment. I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage.

What I Liked

It captures the essence of being on an American road-trip perfectly

The poodle Charley and his interactions with John Steinbeck are hilarious.

It has that exceptional lyricism that all of John Steinbeck’s books have. It’s a simple story, but a great, observant writer wrote it. If the same story had been written by someone else, it wouldn’t have been as good.

I enjoy the historical commentary about things going on at the time, like nuclear submarines, Kennedy, Nixon, and Krushchev.

His admiration for the American worker.

What I Disliked

The book claims to be nonfiction but does feel fictionalized at times. I don’t mind the half-fictionalization, though.

Notes

Setting

On the open road in 1960s America

Characters

*John Steinbeck**: This book’s famous author before he won the Pulitzer prize. He doesn’t talk about himself much in the book, so we get a sense of who he is by what he does. You can tell he thinks of himself as a manly man who critiques the idea that men should take life easier and soften up. He’s mostly an objective observer and interviewer of people he meets in the book, but he sometimes can’t help but give his opinion.

*Charley**: John Steinbeck’s faithful standard poodle accompanies him on his journey around America.

I took one companion on my journey—an old French gentleman poodle known as Charley. Actually his name is Charles le Chien. He was born in Bercy on the outskirts of Paris and trained in France, and while he knows a little poodle-English, he responds quickly only to commands in French. Otherwise he has to translate, and that slows him down. He is a very big poodle, of a color called bleu, and he is blue when he is clean. Charley is a born diplomat. He prefers negotiation to fighting, and properly so, since he is very bad at fighting. Only once in his ten years has he been in trouble—when he met a dog who refused to negotiate. Charley lost a piece of his right ear that time. But he is a good watch dog—has a roar like a lion, designed to conceal from night-wandering strangers the fact that he couldn’t bite his way out of a cornet de pa-pier. He is a good friend and traveling companion, and would rather travel about than anything he can imagine. If he occurs at length in this account, it is because he contributed much to the trip. A dog, particularly an exotic like Charley, is a bond between strangers. Many conversations en route began with “What degree of a dog is that?”

*Rocinante**: Steinbeck’s camper van, named after Don Quixote’s horse.

I wanted a three-quarter-ton pick-up truck, capable of going anywhere under possibly rigorous conditions, and on this truck I wanted a little house built like the cabin of a small boat. A trailer is difficult to maneuver on mountain roads, is impossible and often illegal to park, and is subject to many restrictions. In due time, specifications came through, for a tough, fast, comfortable vehicle, mounting a camper top—a little house with double bed, a four-burner stove, a heater, refrigerator and lights operating on butane, a chemical toilet, closet space, storage space, windows screened against insects—exactly what I wanted.

I was advised that the name Rocinante painted on the side of my truck in sixteenth-century Spanish script would cause curiosity and inquiry in some places. I do not know how many people recognized the name, but surely no one ever asked about it.

Background

It was published in 1962, shortly after the author’s death.

His travels start in Long Island, New York, and roughly follow the outer border of the United States, from Maine to the Pacific Northwest, down into his native Salinas Valley in California across to Texas, through the Deep South, and then back to New York. Such a trip encompassed nearly 10,000 miles and took ten weeks.

He won the Pulitzer year and the Nobel prize for Grapes of Wrath shortly after Travels with Charley was published.

Themes

The importance of companionship and relationships

The beauty of nature and the open road

The tribulations of aging

The power of memory

The importance of first hand experience

book notes

The book is divided into three sections: “Looking for America,” “Finding America,” and “America Observed.”

In the first section, Steinbeck describes his motivation for the journey and preparations. He also reflects on his travels and the changes he has seen in America.

In the second section, Steinbeck details his travels across America. He describes his interactions with a variety of people, from truckers and hitchhikers to police officers and politicians. He also includes Charley’s perspective on the trip and his observations about the people and places he encounters.

Long island to Conneticut

Submarines are armed with mass murder, our silly, only way of deterring mass murder

Do nuclear weapons limit political discussion?

He talked with a sailor stationed on a submarine in New London, Connecticut, and was surprised the sailor enjoyed being on the submarine because it was “futuristic.”

Maine

I have always heard that Maine people are rather taciturn, but for this candidate for Mount Rushmore to point twice in an afternoon was to be unbearably talkative. He swung his chin in a small arc in the direction I had been traveling. If the afternoon had not been advancing I would have tried for another word from him even if doomed to failure. “Thank you,” I said, and sounded to myself as though I rattled on forever.

He visited small-town shops and restaurants and listened to the local radio.

He visited “Abercrombie and Fitch,” an outdoor supply store back then. I thought that was funny.

Upstate New York and Niagara Falls

He comments on how much more freely strangers spoke to each other here and how different people were everywhere he went.

He meets truck drivers at rest stops and notes how they are like the men he met at sea.

Midwest

He discusses new technology, like televisions and mobile homes. He interviews families that live in mobile homes and notes how easily you can move to a new place or for a job.

Wisconsin and North Dakota

He visits Sauk Centre, st Paul, and Minneapolis

He notes how people are afraid to speak out against the government and are conformist

Nobody can find fault with you if you take out after the Russians. You think then we might be using Russians as an outlet for something else, other things. Why, I remember when people took everything out on Mr. Roosevelt

Montana, Yellowstone, Idaho, and Washington

He visits Custer, the battlefield of Little Big Horn, Yellowstone, and the Great Divide in the Rocky Mountains.

I am in love with Montana, It seemed to me that the frantic bustle of America was not in Montana

Yellowstone National Park is no more representative of America than is Disneyland. This being my natural attitude, I don’t know what made me turn sharply south and cross a state line to take a look at Yellowstone. Perhaps it was a fear of my neighbors. I could hear them say, “You mean you were that near to Yellowstone and didn’t go? You must be crazy.” Again it might have been the American tendency in travel. One goes, not so much to see but to tell afterward.

He points out that all the Americans he speaks to wonder about life elsewhere.

He thinks about what it was like for Lewis and Clark to travel through these lands and what they would think of the modern man

It is impossible to be in this high spinal country without giving thought to the first men who crossed it, the French explorers, the Lewis and Clark men. We fly it in five hours, drive it in a week, dawdle it as I was doing in a month or six weeks. But Lewis and Clark and their party started in St. Louis in 1804 and returned in 1806. And if we get to thinking we are men, we might remember that in the two and a half years of pushing through wild and unknown country to the Pacific Ocean and then back, only one man died and only one deserted. And we get sick if the milk delivery is late and nearly die of heart failure if there is an elevator strike

Seattle, Oregon, and California

He notes how much Seattle has industrialized since he last visited.

I wonder why progress looks so much like destruction.

He meets up with a friend from his hometown bar and hears about how everything has changed and all his old friends have passed on.

Let us not fool ourselves. What we knew is dead, and maybe the greatest part of what we were is dead. What’s out there is new and perhaps good, but it’s nothing we know.

“I will now tell you true things, brother-in-law. Step into the street—strangers, foreigners, thousands of them. Look to the hills, a pigeon loft. Today I walked the length of Alvarado Street and back by the Calle Principál and I saw nothing but strangers. This afternoon I got lost in Peter’s Gate. I went to the Field of Love back of Joe Duckworth’s house by the Ball Park. It’s a used-car lot. My nerves are jangled by traffic lights. Even the police are strangers, foreigners. I went to the Carmel Valley where once we could shoot a thirty-thirty in any direction. Now you couldn’t shoot a marble knuckles down without wounding a foreigner. And Johnny, I don’t mind people, you know that. But these are rich people. They plant geraniums in big pots. Swimming pools where frogs and crayfish used to wait for us. No, my goatly friend. If this were my home, would I get lost in it? If this were my home could I walk the streets and hear no blessing?”

And Carmel, begun by starveling writers and unwanted painters, is now a community of the well-to-do and the retired. If Carmel’s founders should return, they could not afford to live there, but it wouldn’t go that far. They would be instantly picked up as suspicious characters and deported over the city line.

Arizona, New Mexico, Texas

He passes through Arizona and New Mexico but spends most of his time in Texas.

When I started this narrative, I knew that sooner or later I would have to have a go at Texas, and I dreaded it. I could have bypassed Texas about as easily as a space traveler can avoid the Milky Way. It sticks its big old Panhandle up north and it slops and slouches along the Rio Grande. Once you are in Texas it seems to take forever to get out, and some people never make it.

Steinbeck describes how Texas is different than all other states.

Texas is a state of mind. Texas is an obsession. Above all, Texas is a nation in every sense of the word. And there’s an opening covey of generalities. A Texan outside of Texas is a foreigner. My wife refers to herself as the Texan that got away, but that is only partly true. She has virtually no accent until she talks to a Texan, when she instantly reverts. You would not have to scratch deep to find her origin. She says such words as “yes,” “air,” “hair,” “guess,” with two syllables—yayus, ayer, hayer, gayus. And sometimes in a weary moment the word ink becomes ank.

Most areas in the world may be placed in latitude and longitude, described chemically in their earth, sky and water, rooted and fuzzed over with identified flora and people with known fauna, and there’s an end to it. Then there are others where fable, myth, preconception, love, longing, or prejudice step in and so distort a cool, clear appraisal that a kind of high-colored magical confusion takes permanent hold. Greece is such an area, and those parts of England where King Arthur walked. One quality of such places as I am trying to define is that a very large part of them is personal and subjective. And surely Texas is such a place.

I have moved over a great part of Texas and I know that within its borders I have seen just about as many kinds of country, contour, climate, and conformation as there are in the world saving only the Arctic, and a good north wind can even bring the icy breath down. The stern horizon-fenced plains of the Panhandle are foreign to the little wooded hills and sweet streams in the Davis Mountains. The rich citrus orchards of the Rio Grande valley do not relate to the sagebrush grazing of South Texas. The hot and humid air of the Gulf Coast has no likeness in the cool crystal in the northwest of the Panhandle. And Austin on its hills among the bordered lakes might be across the world from Dallas.

New Orleans and Mississippi

He travels to New Orleans and witnesses the conflict of desegregation in the south. He witnessed the schools desegregating, the people protesting integration by shouting at children while they tried to go to school, and the crowds gathered to watch.

A group of stout middle-aged women who, by some curious definition of the word “mother,” gathered every day to scream invectives at children. Further, a small group of them had become so expert that they were known as the Cheerleaders, and a crowd gathered every day to enjoy and to applaud their performance. This strange drama seemed so improbable that I felt I had to see it. It had the same draw as a five-legged calf or a two-headed fetus at a sideshow, a distortion of normal life we have always found so interesting that we will pay to see it, perhaps to prove to ourselves that we have the proper number of legs or heads. In the New Orleans show, I felt all the amusement of the improbable abnormal, but also a kind of horror that it could be so.

These blowzy women, with their little hats and their clippings, hungered for attention. They wanted to be admired. They simpered in happy, almost innocent triumph when they were applauded. Theirs was the demented cruelty of egocentric children, and somehow this made their insensate beastliness much more heart-breaking. These were not mothers, not even women. They were crazy actors playing to a crazy audience.

Conclusion and Return to New York

The third section contains Steinbeck’s reflections on what he has learned from his journey. He discusses the differences he observed between the America of his youth and America of the 1960s. He also describes the changes he saw in himself and how the journey has affected his view of his country and its people.

John Steinbeck points out how no two trips and individuals are alike; his trip is his experience of America and is not meant to be definitive.

After navigating the entire country, he gets lost right before getting home.

I said, “Officer, I’ve driven this thing all over the country—mountains, plains, deserts. And now I’m back in my own town, where I live—and I’m lost.”